Proteins with complex binding modes

Simplified single motif discovery problem

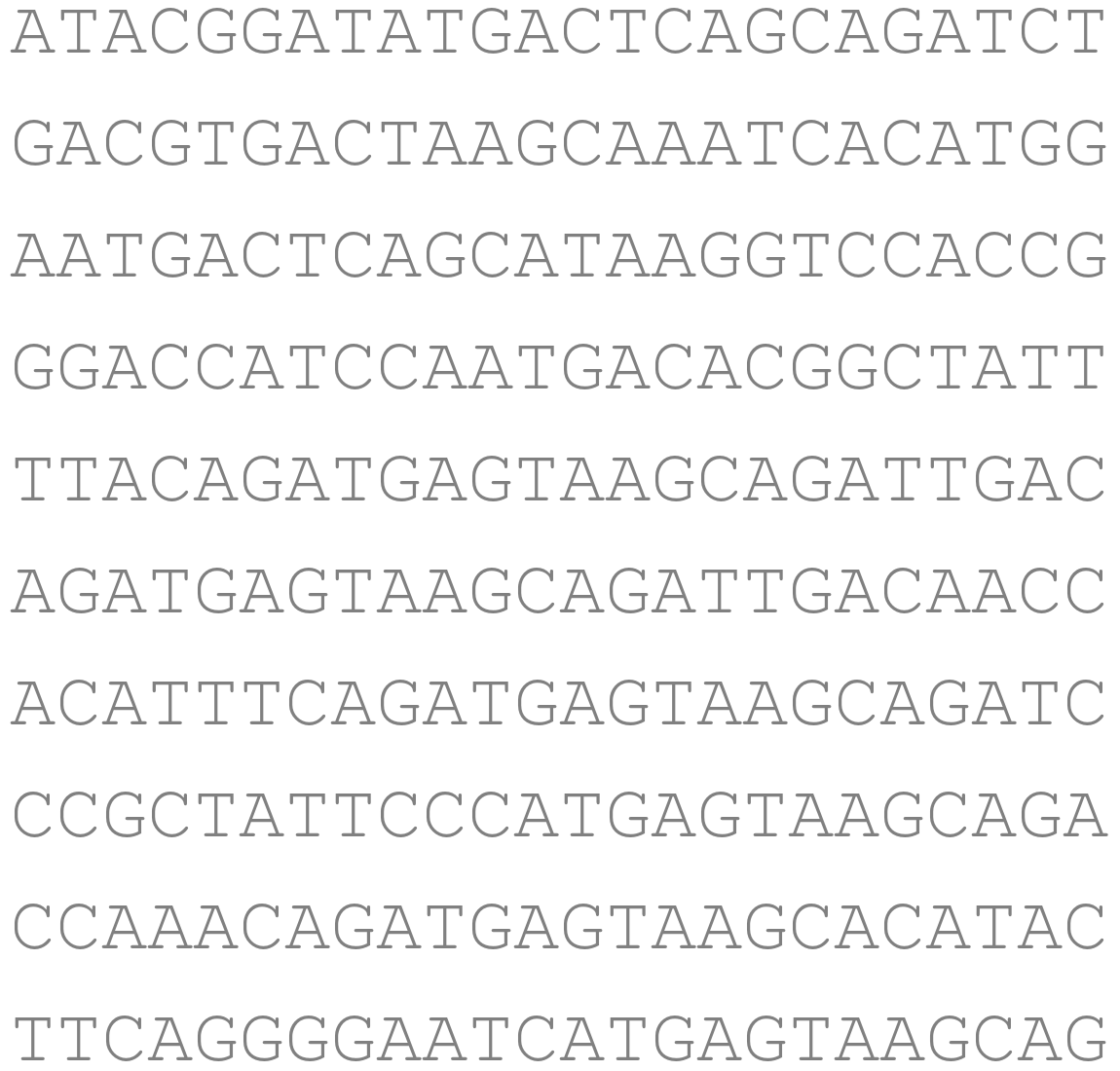

In the motif discovery problem, an example dataset will look exactly like:

i.e., a dataset whose entries are all DNA strings.

This dataset usually is obtained from a sequencing experiment, e.g., Chip-Seq.

In addition, this dataset is associated with a protein. The assumption is that this protein tends to bind to a set of similar DNA substrings embedded in those DNA strings (In biology it's colloquially called the protein's binding specificity), and we need to find out where those substrings occurred.

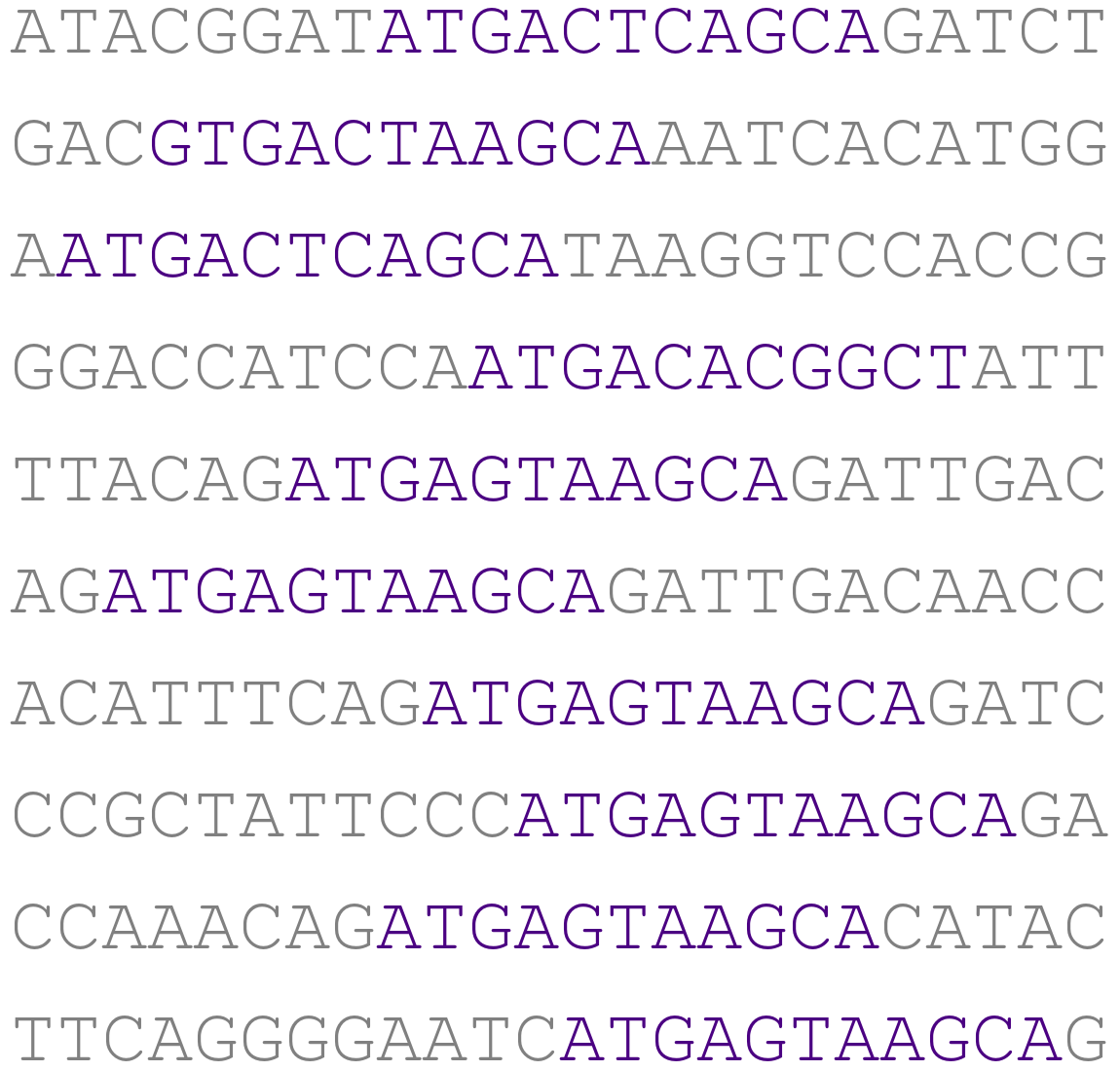

Let's assume we possess a well-defined problem formulation alongside an effective algorithm for identifying this set of similar string – referred to as the purple substrings in the dataset:

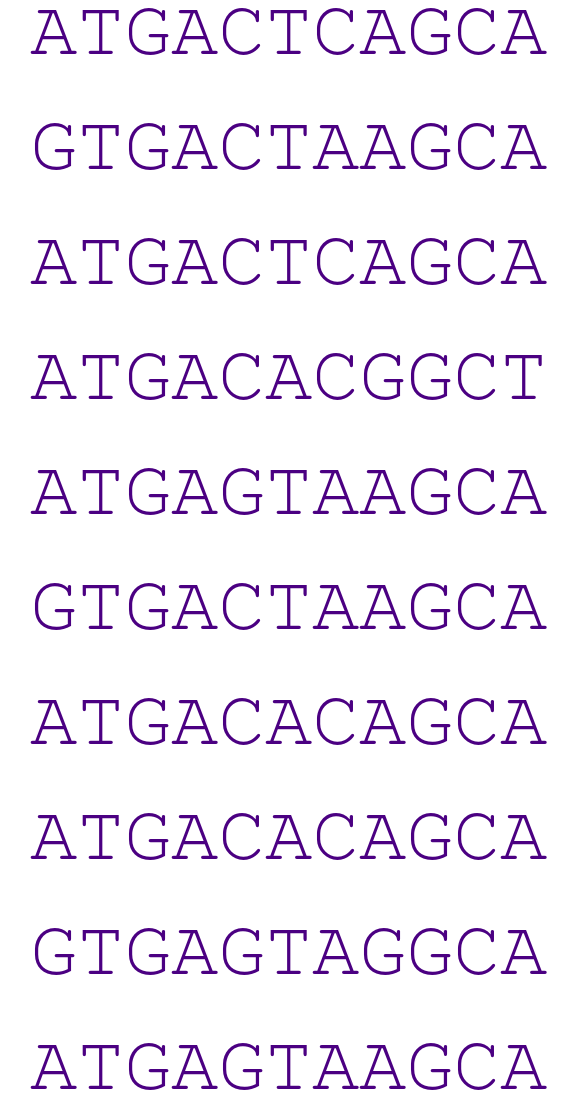

We can then turn them into a multiple sequence alignment (MSA):

This MSA, in turn, can be made into a position weight matrix (PWM) .

We estimate the position weight matrix by first using the empirical frequency of each nucleotide at each position from the MSA. This step is equivalent to doing a maximum likelihood estimate of the parameters of a product multinomial distribution. Then, we fill each -entry of the PWM by , where is the assumed genomic background frequency for nucleotide .

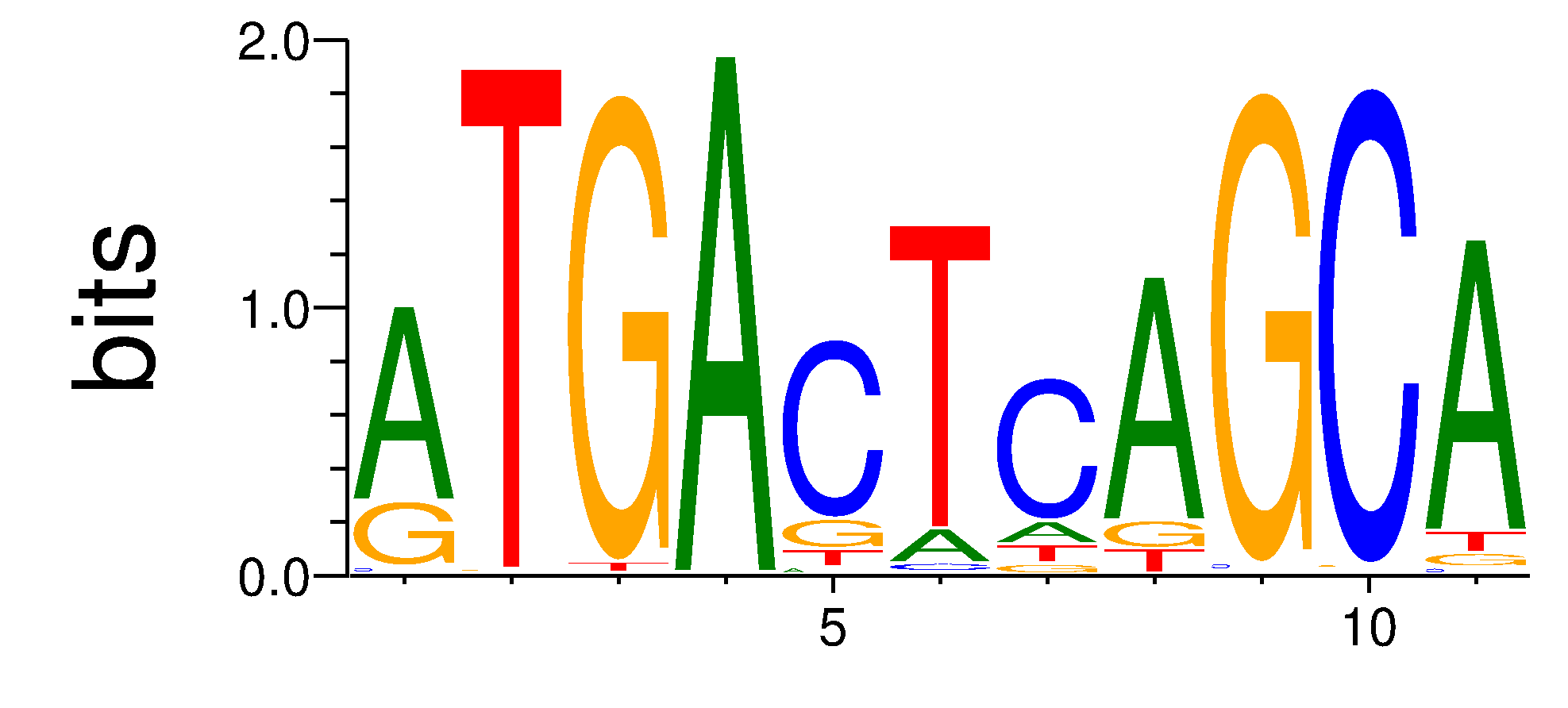

We can visualize the PWM in the following picture:

where the height of the nucleotide at each column shows how conserved each nucleotide is at each position. The higher the nucleotide, the more conserved; each -th column's height is given by the so-called information content formula, i.e., .

However, the motif discovery problem becomes significantly more intricate when considering the mechanism by which proteins bind to DNA.

Complex binding modes

Here, we present qualitative characterizations of various binding modes along with illustrative examples sourced from the study by Siggers and Gordan.

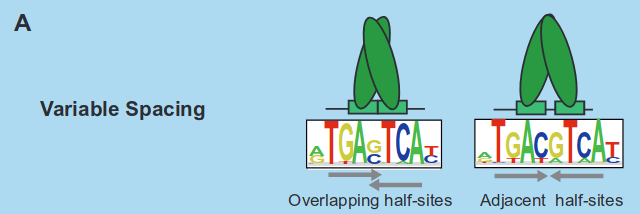

One complex mechanism through which a protein can bind to DNA is via variable spacing:

In variable spacing, the binding sites are fragmented into distinct parts. It's a common biological terminology to denote the separation between these parts as a spacer when a protein binds to the DNA.

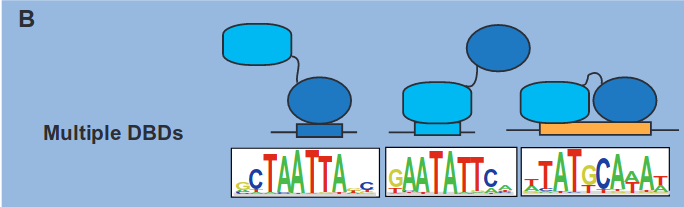

Another scenario involves multiple DNA binding domains (DBDs):

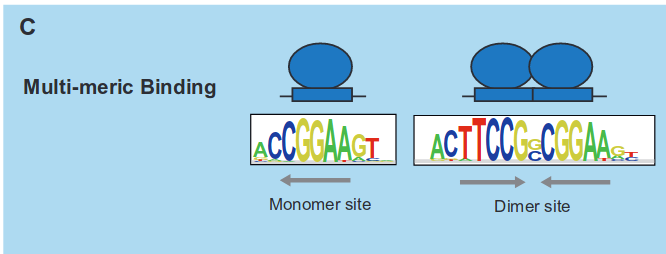

In cases of multiple DBDs, a protein may possess distinct binding sites across its structure. Additionally, we can also have a situation called multimeric binding:

In multimeric binding, once more, the protein features more than one binding site. However, in this scenario, one binding site represents an extended version of another, meaning that the binding sites overlap.

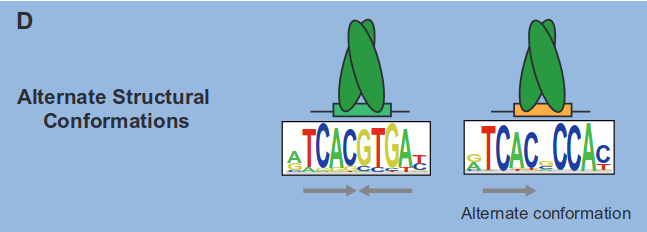

Last, we have alternate structural conformations:

In summary, these situations, encompassing binding modes such as variable spacing, multiple DBDs, multimeric binding, and alternate structural conformations, collectively render motif discovery significantly more intricate than the simplified version of the problem discussed earlier.

Moreover, these binding modes for a protein may not necessarily be mutually exclusive. For instance, a protein could exhibit binding modes that encompass both multimeric binding and variable spacing.

Detecting motifs characterized by the aforementioned binding modes presents a computational challenge. In the upcoming series of blog posts, we will outline our approach to identifying these complex binding patterns.

References

- Trevor and Gordan Siggers, Protein--DNA binding: complexities and multi-protein codes, 2014.

This work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Last modified: December 19, 2025.

Website built with Franklin.jl and the Julia language.